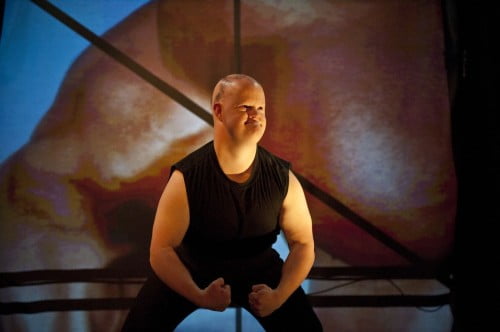

Image: Force Majeure’s Nothing to Lose. Photo by Heidrun Lohr

Running from 10-22 March, the biennial contemporary dance festival Dance Massive features works across several locations – the two Arts House venues in North Melbourne, Carlton’s Dancehouse, and the Malthouse Theatre in Southbank. Our team of reviewers will be sharing their thoughts on the festival here, with reviews updated regularly. We invite you to share your own thoughts on the shows you’ve seen in the comments below.

Merge

Merge opens with four dancers emerging from a collective cocoon. In the early moments they are more objects with legs than people and I was reminded fo the fabulous work of the Swiss puppetry company Mummenschanz, who animate objects with extraordinary emotional content.

Merge works with objects too but, while it is a technically accomplished work, it fails to bring emotionality to its subject matter.

As the dancers detach from their bundles and drag them to the edges of the stage they begin a 50-minute exploration of the human relationship with the object. The work is more a series of sequences than a narrative although it moves towards a rather too literal apocalyptic conclusion in which the dancers are trapped and suffocated by the material world.

Many of the seqences are original and all of them are polished. The dancers work with rods in lovely fluid movements, use a folding mat in series of creative testing motions and ape machine vibration amusingly with considerable skill. There are a couple of impressive balances and some fine group movements.

But the work feels gymnastic and self-conscious rather than communicative. It is an intellectual and physical construction which lacks heart. The performers were disciplined and the choreography was clever but in a rich festival of dance offerings Merge fails to make an argument for itself.

Merge

by Melanie Lane

Arts House, Meat Market

18 to 22 March

Rating: 3 starts out of 5

Reviewed by Deborah Stone

Nothing to Lose

Co-created with fat activist Kelli Jean Drinkwater, Nothing to Lose – Kate Champion’s final work with Force Majeure, the company she established in 2002 – is a compelling reclamation of the stage by performers whose girth usually banishes them from it. The results are revelatory. Stripped down to their underwear, virtually every inch of their fleshy bodies on show, the performers remind us – defiantly and proudly – just how narrow and restrictive our traditional definitions of beauty are.

The production wholeheartedly embraces the performers’ physicality, typified by a sequence in which one of the women repeatedly throws herself down on the stage, accompanied by a soundtrack of screams. Embodying frustration, this sequence also speaks powerfully of liberation; of the freedom that comes with rage.

Earlier in the piece, select audience members are invited onstage to touch the dancers; elsewhere, the dancers themselves wobble, manipulate and play with their bodies. For some, such sequences may veer uncomfortably close to a freak show, but the overall effect – as with a later sequence which confronts us with the insults flung the performers’ way – is to humanise people whom society invariably stigmatises.

One of the strongest moments in Nothing to Lose comes as its large-bodied dancers turn their gaze upon the audience. Instead of being scrutinised, suddenly they are scrutinising us, challenging us, daring us to laugh or mock or pity. It’s a startling reversal, and one of many powerful elements of this provocative, thoughtful and beautifully crafted show.

Force Majeure’s Nothing to Lose

The Coopers Malthouse, Southbank

11-21 March

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

Reviewed by Richard Watts

Maximum

The physical limits of our bodies are most commonly tested in marathons, body building competitions, abseiling, and extreme sports, yet the same endurance is required in dance, though often not categorised in the same way.

In Maximum, choreographer and performer Natalie Abbott places two disparate physical forms – a bodybuilder and dancer – side by side to demonstrate the physical exhaustion experienced by each.

In a stark white room lit with rows of almost blinding industrial fluorescent lights, we walk in on the duo enacting what could be a warm up to a wrestling match, with a look of exhaustion already visible on their faces. A water bottle is found under each seat, and we take our positions as spectators. The performers’ panting breath, and the rhythmic squeaks of their Nike sneakers overlay a score that resembles white noise.

After a momentary pause, the two begin to circle the set in unison. Continuing for countless laps, they progress to a jog, the dancer’s slight shoulders and long limbs in stark contrast to the bodybuilder’s bulging muscles; yet together they are not so different. The duo continue almost tirelessly, interrupting their trance only to recuperate before returning to a jog, sidestep, or crossing one foot over the other before they split to move across the set individually.

A sudden yell from the dancer and the set turns black. When the light returns, we are greeted by their red and blotchy faces as they continue with a series of stamina-testing exercises. A series where the duo are on all fours making woofing noises – or is it dry heaving? – as they each lift their pelvis up and down adds to the audience’s confusion and restlessness. Are we being tested, too?

It felt exhausting watching the pair as drops of sweat dripped from their brows. Microphones positioned at opposing ends of the set amplified the thumps of their footsteps, echoing like heartbeats. In a final sequence, we witness the dancer lifted on the bodybuilder’s thighs, her back to him as he slowly turns and she stretches out her arms and curves her feet as if trying to grasp a balloon that will lift her into the air. She slips, and this sequence of climbing, falling, and refocusing repeats until there is complete darkness and a deafening whistle to conclude the performance.

Though confidently exploring how endurance, fear and exhaustion are experienced, through relentless repetition Maximum spawns such feelings in the audience, too. Exercise as performance art was clearly demonstrated through the dancer’s ability to keep pace with the bodybuilder, but I wanted to see more dance and fluid movement from the bodybuilder. Though innovative, there was a curiosity, and a desire to be surprised, that was not quite satisfied.

Maximum

by Natalie Abbott

Dancehouse

14-17 March

Rating: 3 out of 5 stars

Reviewed by Madeleine Dore

Catalogue

The ways in which our identities are created, singly and in relation to one another, is a perfect topic for this remarkably accomplished work by mixed-ability performance company Rawcus.

Catalogue features as part of the Dance Massive festival but it is certainly not simply dance. The work is a skilful blend of theatrical performance, visual art, design and movement exploring the multiplicity of individual identities.

The set consist of 8 stark cubes, stacked in two rows of four on top of one another. As they are illuminated singly or in groups we are introduced to individuals whose personal variations are far more significant than the stark labels of ‘disabled’ or ‘able-bodied’ would suggest.

These live performances are supported by the use of striking photographic portraits projected in the cubes, and by a vivid and eclectic soundscape constructed by Jethro Woodward.

The players begin by running and towards the end of the work it becomes clear that they are in pursuit of their own identities. In the course of the work we are asked to consider the many ways our identities can be defined by gender, name and age but also by belief or habit and – most significantly – by the relationships we have.

In most of the work the performers are isolated in their cubes but as they communicate in words, mirror one another in movements or respond to outside stimulus their selves are revealed in their responses.

The work sags a little about two thirds of the way through and becomes a little repetitive but it revives with striking new segments including one of the tenderest moments, a graceful pas de deux between a man in a wheelchair and an able-bodied woman. Their movements mirror those of an able-bodied couple in another cube but are much more compelling with their other-worldly beauty.

Director Kate Sulan has done an extraordinary job getting the most from such a varied group of performers and creating a work of beauty and meaning. I hope this work draws an audience far beyond those who might usually attend work by a mixed-ability company.

Catalogue

by Rawcus

Arts House, Meat Market

10-14 March

Four stars out of five

Reviewed by Deborah Stone

Depth of Field

Dancers swim and spin in clouds of dust on the sandy forecourt outside the rust-red building housing Chunky Move and the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, as curious passers-by look on. A slow shoulder-roll, head pressed close to the gritty surface; a controlled fall, dancers kneeling in the dirt as dust clouds rise around them; Melbourne’s cityscape seen anew beneath the setting sun.

Tension, release; pursuit, surrender – familiar urban rhythms are accompanied by a cinematic score composed by Ben Frost, Daniel Bjarnason and The Bug, which thanks to sound designer Marco Cher-Gibard incorporates live sound in real time: a foot or a face on gravel, a passing tram, a helicopter flying low overhead. The city and its people become part of the show, with compelling results.

Though its climax feels over-extended due to a series of false endings, Depth of Field features moments of true dance magic, as well as being technically adept and deftly performed. For this reviewer, it is Anouk van Dijk’s most accomplished work since 2012’s An Act of Now.

Chunky Move’s Depth of Field

The Coopers Malthouse, Forecourt

6-14 March

Rating: 4 stars out of 5

Reviewed by Richard Watts

Long Grass

Ambitious and challenging, Vicki Van Hout’s long-gestating dance-theatre work Long Grass – exploring the lives of Indigenous people living ‘long grass’ in and around Darwin, for whom the term ‘homeless’ is an uneasy fit – is at its best in moments of pure dance, such as a sequence in which the humidity and tension of the ‘build-up’ breaks and the wet season commences. Bodies thrust and stomp, heads swinging, all power and tempest and heightened emotion. It’s a scene of undeniable impact – as is a subsequent sequence exploring the tragic consequences of sexual violence.

There is humour in the work too, thanks in part to the live voiceover and score played by two musicians seated just offstage, one of whom is Gary Lang, the work’s cultural consultant.

Elsewhere, its many elements – including props, projection, and a sometimes laboured narrative – fail to cohere. Overall, one comes away from Long Grass with a sense of the art of the piece being of lesser importance than its message. Greater subtly, and more successful integration of its various components is required for the piece to have any lasting impact beyond a sometimes-blunt retelling of tragedy.

For an alternate take on Long Grass read ArtsHub reviewer Lynne Lancaster’s thoughts on the production’s Sydney Festival season, here.

Vicki Van Hout’s Long Grass

Arts House, Meat Market

10-14 March

Rating: 3 stars out of 5

Reviewed by Richard Watts

Dance Massive 2015

www.dancemassive.com.au

10-22 March