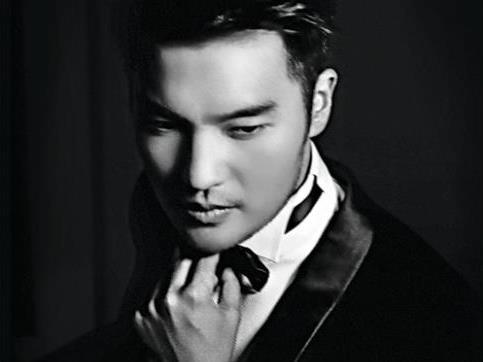

Violinist Ray Chen; image: www.mso.com.au.

The MSO was in fine form on Friday night under the direction of its Chief Conductor, Sir Andrew Davis. The program was an extensive and ambitious one, commencing with Ralph Vaughan Williams’s touching, impressionistic Serenade to Music, a setting of a passage from Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice, followed by Tchaikovsky’s troublesome Violin Concerto and finally Richard Strauss’ majestic Alpine Symphony.

It was a pleasure to hear the MSO Chorus on this occasion singing the Vaughan Williams, evidently most carefully rehearsed by its new chorus master, Anthony Pasquill. I have not heard the ensemble sound more unified and responsive to Davis’s clear, expert direction, while particular accolades go to the sprightly sopranos who sang with accuracy, near-faultless purity of tone, vigour and courage. It is hoped that further tenors and one or two more true basses might be persuaded to join the ranks of the chorus in due course. It was the first time I had heard the work performed with choir (and not 16 soloists); there were surprising pleasures and few disappointments. Suffice to say that the choral version occasionally stretched the limits of only a few of the singers. The work is suitably bathed in soft stillness and moonlight with notable cushion of subtly blended strings, strumming harp and a magnificent violin solo played with keen accuracy and much sensitivity, if somewhat shy of rapture, by concertmaster, Dale Barltrop. Sir Andrew conducting this music was as smooth as riding through Yorkshire in a Rolls Royce.

Ray Chen has the makings of stardom. With two internationally important competition wins after graduating from the world-renowned Curtis Institute, a major recording label behind him, a New York agent, premium marketing and the loan from the Nippon Foundation of a priceless Stradivarius violin once owned by Joachim, this is certain. Outfitted by Giorgio Armani and maintaining a busy social media profile, Chen hopes to attract younger audiences to Classical music, and good luck to him for that.

Written in the midst of the composer’s fervent emotional turmoil while staying on Lake Geneva recovering from a failed marriage and suffering non-requited passion for a young violinist, Josef Kotek, the Violin Concerto became something of an unwanted ‘child’, being passed from one soloist to another. Chen’s approach to the first movement was almost as a declamatory recitative with everything fluid, gestural and somewhat more moderato than usual. Davis indulged the soloist’s interpretation, eager to move things on when possible. The Canzonetta was conveyed with full sympathy and the Finale with virtuosity and flair. What was notable throughout was beauty of tone, enhanced by this truly marvellous instrument, telling care and accuracy of tuning. It has to be acknowledged as well that Chen is undoubtedly a very fine stage presence with the poise and elegance of youthful confidence from an emerging talent. With time we may expect a growth in emotional maturity. Such was the explosive enthusiasm of the audience, the soloist returned to the stage nine times and performed two encores – Paganini’s 21st Caprice, Op 1 and Bach’s famous Gavotte en rondeau from his Partita No 3 for solo violin, BWV 1006 – delaying the second, substantial half by twenty minutes.

Strauss’s snow-capped tone poem, an orchestral colossus, is a mighty expanse to traverse. Its musical language may be tonally less adventurous than Salome and Elektra written over the decade prior, but requiring some 137 players, this 22-movement work lasting nearly an hour certainly packs a punch. Along with brute force, thump and bluster the work can also be fragile, and a fine performance depends on an innate understanding of the late-nineteenth-century, Austro-German tradition, particularly Viennese, of rhetoric and gesture. Luckily, Davis has had a very close association with the work for decades (his 1981 recording with the London Philharmonic Orchestra is considered important) and he negotiated all of this with considered surety and close attention to detail. I felt that on this occasion his vision wasn’t fully absorbed by the orchestra, it being so early in the season; occasionally the reading struggled for buoyancy and narrative connection. Praise, however, should go particularly to principal oboist Jeffrey Crellin whose musicianship shone out like the Rheingold, lower brass, and the percussion section: the celeste, thunder machine and cow bells were all memorable. My only reserve was the quality of the sound of the digital organ which did not produce a timbre that could be compared to anything like the sound or feel and presence of a real instrument; sadly, as part of the recent renovations, Hamer Hall’s grand organ no longer exists. Concluding at 10.30pm the concert had many elated yet anxious patrons running to later trains and buses.

Rating: 3.5 stars out of 5

An Alpine Symphony: Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Vaughan Williams

Tchaikovsky

R. Strauss

Andrew Davis, conductor

Ray Chen, violin