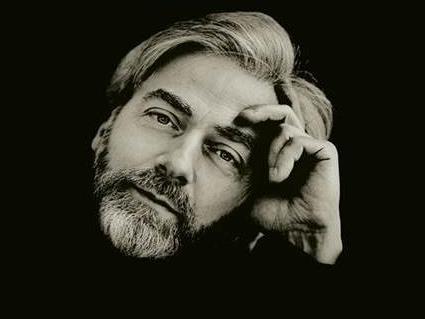

Cover art: Franz Schubert/Krystian Zimerman/Piano Sonatas D 959 & D 960. Photograph of Krystian Zimerman via Deutsche Grammophon.

Krystian Zimerman is a unique artist and regarded as one of the greatest living pianists. At 18 he won first prize in the 1975 International Chopin Competition in Warsaw. Now residing in Basel, Switzerland, he has an exclusive life-long recording contract with Deutsche Grammophon though he very rarely records. Almost all of his few recordings have achieved international acclaim and some are now regarded as definitive classics. His last solo recording was made in February, 2009 (Bacewicz’s Piano Sonata No 2) and before that in August, 1991 (Debussy’s Préludes). The recording internationally released today was made in the new Kashiwazaki City Performing Arts Center Art-Forêt, Japan in January last year. Like several artists of his stature (for example, Perlman and Sokolov), owing to often facile and banal marketing and promotion he shuns publicity and interviews entirely. It is clear though that he welcomes serious, sensitive and authentic conversation about music; intelligently informed dialogue about Art and its role in our shared humanity.

Why so few recordings? Zimerman contends that in our current age of compressed time and digital recording technology, Art music has died within the sterile and artificial environment of the recording studio: ‘Digital technology so clearly conveys the sound that you can’t hear the music any more. Music is something more than audio.’ He continues that we have become accustomed to disinfected ‘perfection’ and homogeneity of style (‘I call it mid-Atlantic’) that has no connection to specific cultural reference. This recording, using 32-bit technology, came about after Zimerman provided a benefit concert after an earthquake in Kashiwazaki in 2007 and by way of gratitude the hall was made available for a week for this project last year. The acoustician for the newly built hall was a student of Yasuhisa Toyota who designed Suntory Hall in Tokyo. Of its acoustic qualities Zimerman says, ‘…every note is clear, yet each is in a cushion of warm surroundings.’ Severely self-critical, he believes that if a recording is made it should enrich the listener and not replicate what has been achieved and said before. It is somewhat disconcerting to learn that he cannot tolerate listening to his own recordings, as fine as they are: ‘I am not happy with recording at all…I have to listen to them once to approve and then that is it.’

Zimerman is no concert promoter’s dream artist either. He cannot decide on a program until close to the concert: ‘How do you make a decision about what you eat in a restaurant…do you know this one year in advance?’ Programs are announced as late as possible. And like great pianists of the past (for example, mentor Arthur Rubinstein) he has travelled since 1989 only on the condition that his own instruments and/or separate, particularly-voiced keyboards accompany him, matching the repertoire he is performing. Ever since he started repairing his own pianos, through financial necessity as a student in Poland, Zimerman has had a fascination for the technology of touch and voicing of the instrument.

After the attacks in New York on 11 September 2001, Zimerman was justifiably angry that two of his instruments were destroyed as a result of heightened security inspection protocols. Added to that, his politically sensitive announcements following his recitals in America – ‘Weapons are not a way of solving problems. Wars are created by cowards.’ etc – have made him unpopular with promoters there and Zimerman finally decided in 2009 to no longer perform in North America.

This is his first recording of the final two Sonatas by Franz Schubert. The works were written only months before the composer’s death in November, 1828. Schubert was suffering from ill-health: weakness, swelling, dizziness and nausea. Both compositions were written between Spring and Autumn of the composer’s last year. ‘I had such respect for these works and for the late sonatas of Beethoven, but with that came tremendous fear…I realised it was time, as I came to a new stage in my own life, to find the courage to perform these late works. I let go of the old stories about this being music by a man aware that he was about to die. Schubert was ill, yes, but he was still in very good shape and filled with a wonderful sense of humour when he wrote what proved to be his final sonatas. I am sure he was looking ahead. The Sonata in A major, for example, is such a modern work. And it has so much to say about life here, as does the Sonata in B flat major.’

First and foremost what struck me with this recording was the virtuosity and artistry of this extraordinary artist, the strong, well worked-through and clear conviction of his interpretation. But next came the sound quality, voicing and touch of the instrument. Although performed presumably on a Steinway, with Zimerman’s own keyboard inserted the instrument sounds as a historic Viennese instrument, perhaps a Conrad Graf with its thin soundboard and light leather-capped hammers. Clear and transparent articulation is prominent in this recording from the scalar runs of the opening Allegro of the A major Sonata. He describes the voicing and action as follows: ‘Compared to a modern grand piano, the hammer strikes a different point of the string, enhancing its ability to sustain a singing sound – though it does also set up different overtones and the piano may sound strangely tuned. Also, the action is lighter.’

Zimerman gives scrupulous attention to the smallest details. Transparent textures are achieved from very little use of the sustain pedal. Every note and every phrase means something distinct and specific. Every bar is considered highly precious and nothing is allowed to be ignored nor wasted. There is also a vivid understanding of each work’s architecture.

Highlights include the lamenting Andantino of the A major Sonata that is never wallowing, contrasted by the following Menuetto: Allegro – Trio, Spring-like, buoyant and ebullient. The Molto moderato of the final B flat major Sonata sounds with regal Brahmsian warmth and breadth. The following Andante sostenuto is translucent, having a true sense of tragic inevitability matched with swells of pathos. Zimerman says, ‘the slow movements of the D959 and D960 sonatas are maybe the saddest music I know: the major keys are even sadder than the minor, because this is complete resignation, complete acceptance, perhaps thinking of leaving this planet and ending life.’ The Scherzo: Allegro vivace con delicatezza – Trio of the final sonata provides a carefree, lyrical contrast with the Andante, while the concluding Allegro ma non troppo – Presto discloses a telling sense of introspection offset by an unworried, brightly lit optimism.

Here is luminous and poetic simplicity.

Very highly recommended.

4 1/2 stars out of 5

Franz Schubert/Krystian Zimerman/Piano Sonatas D 959 and D 960

Deutsche Grammophon

00028947975885

Released 8 September, 2017