Matthew Bourne’s contemporary dance production of Lord of the Flies is an extraordinarily ambitious work.

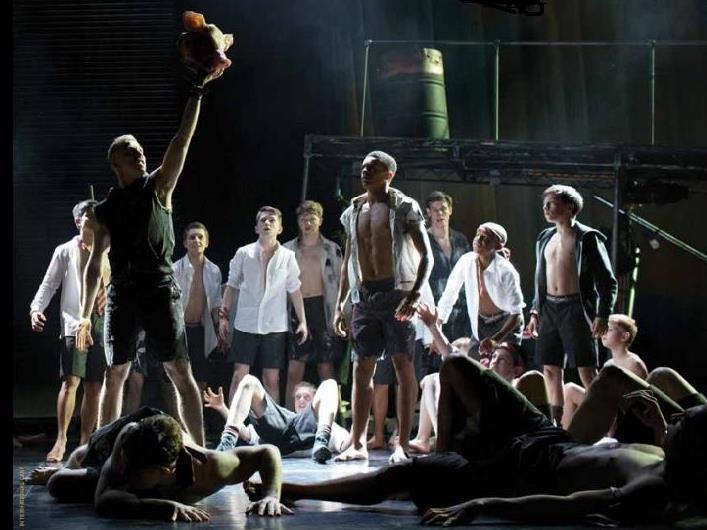

The all-male company consists of nine professional dancers and 23 young dancers, the latter sourced through a community development process designed to provide access and a transformative life experience rather than simply deliver children to the stage.

To have moulded these boys into a disciplined and engaging company of dancers is an extraordinary achievement. The result is worth seeing just to enjoy the capacity of these young people to rise to a challenge and deliver a professional quality production.

That the final result is not wholly satisfying as a dance work is no criticism either of the company or of the process that its dedicated team employed. Many of the boys have little or no dance experience and those that do are more likely to have done a suburban hip-hop class than seen the inside of a professional theatre. On stage they are all energetic, well-trained and engaging. The youngest of them – 10-year old William Gilchrist who plays teddy-bear clutching Percy – is affecting and polished, and every one of them puts his all into the role.

If anything it is the young men in the professional cast who seem to be stymied, lacking the physical space or choreographic challenge to excite us. Ralph (Dominic North) is a striding school prefect, Piggy (Luke Murphy) is nervously nerdy and Jack (Daniel Wright) is a swaggering thug but none of them shines. Perhaps they were discouraged from doing so in a work that is so much an ensemble piece. Or perhaps it is simply too much to expect that on top of it all we would get imaginative choreography or the athleticism that we were hoping for from Bourne’s boys.

Lord of the Flies is, of course, a very well-known novel and the production is determinedly faithful to William Golding’s original story of a group of stranded boys whose society disintegrates into savagery and its contention that we are all only a thin skin away from our animal selves.

Choreographer and co-director Scott Ambler gives a very literal telling of the story, so much so that slabs of the work are more dance-drama than contemporary dance. Aesthetically, this literal retelling is not particularly interesting. It might have been more rewarding had some of the detail been dumped and the creative expression allowed to flow, as it does for example, in the sensitive scene where Simon imagines the pig’s head come to life.

But literalism does give the work accessibility and will enhance its appeal for what I suspect is its target audience, the young people who are both the subject and the natural audience of Lord of the Flies.

They will also enjoy the moments of modernisation, like the amusing scene in which the boys discover they do not have mobile phone access and lose themselves in a forest of flickering lights or the foraging which yields sundry chip packets and chocolate bars. Similarly, the conch is replaced by a drum stick beating an empty Shell petrol drum, changes which transform us from the desert island of the original to a potent context of urban squalor.

Lez Brotherston’s design is a major contribution, providing a good balance between structure and disorder through a slab of terraced scaffolding running diagonally across the stage and sundry petrol drums and wicker baskets. Racks of jackets give us a sense of the shadows of discarded selves that the boys crash through and occasionally upend.

The sound design by Paul Groothuis, music by Terry Davies and lighting design by Chris Davey, are also powerful contributors to the sense of disintegration, fear and animistic instinct at the heart of Lord of the Flies.

But the challenge of organising a rabble to describe a rabble without actually presenting a rabble on stage is not always met. There are many occasions when there is just far too much going on, too many bodies on stage or insufficient direction of the audience’s eye. It’s a mercy to get a break from the slow minimalism of a great deal of contemporary dance but an audience does need to know where to look.

For sophisticated contemporary dance audiences, Lord of the Flies might not quite make the cut. But for that much greater audience ready to be engaged by a dramatic, physical theatrical experience and to applaud the talent of young males, as no doubt for all those involved, it is a great experience.

3 ½ stars out of 5

Lord of the Flies

Presented by Arts Centre Melbourne and Bank of Melbourne

In partnership with Matthew Bourne’s New Adventures & Re:Bourne

Based on the novel Lord of the Flies by William Golding

Music by Terry Davies

Sound design by Paul Groothuis

Lighting design by Chris Davey

Design by Lez Brotherston

Choreographed by Scott Ambler

Adapted and directed by Matthew Bourne and Scott Ambler

State Theatre, Arts Centre Melbourne

5 -9 April 2017