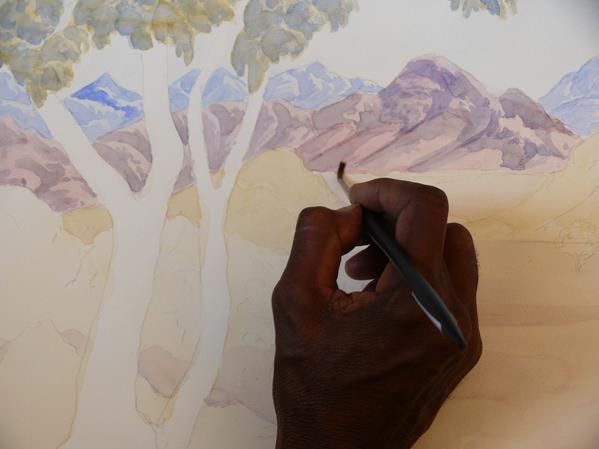

Gloria Pannka working on a watercolour painting in the style established by Albert Namatjira. (Image via Big hART Inc.)

Commercial imperatives, limited time, the brief window when inspiration strikes; there can be a variety of reasons why some artists only work on short-term and small scale projects. But artists who have the opportunity to work on long-term projects are effusive in their praise for such processes.

‘I love it – this is the best work of my career,’ said playwright David Burton, who has been working with the residents of the Isaac Region, in central Queensland, on an ambitious event for Queensland Music Festival (QMF) since October 2016.

Burton, who writes ‘very mainstream plays for state theatre companies in the other half of my time,’ is the writer and director of the QMF event The Power Within, an outdoor musical spectacular featuring a cast of hundreds drawn from local communities across the Isaac Region.

‘I love this work because it’s an act of empowerment – you’re giving the gift of the arts to other people. It’s more than just singing, it’s teaching people how to sing songs and feel happy. It’s about creating a choir in a town where there wasn’t one and that means uniting people who can be friends in a community where previously they were strangers. You see the effect of this happening right in front of you. It’s incredibly satisfying and it’s such fulfilling work,’ Burton said.

QMF has had a long-standing partnership with the Isaac Region and its community since 2005, ensuring a degree of stability in a district shaken by the mining boom and bust.

QMF’s Artistic Director, Katie Noonan, explains: ‘We’ve met people from six towns right across the Isaac Region who are really in an exciting but I guess difficult time of transition – redefining their cultural identity after the mining downturn. I think preconceptions about the future are changing rapidly. It’s a really big time of change and if you can harness the power of music to connect these communities and celebrate the resilience of these communities, that is going to be a very exciting and profound thing.

‘And unlike just coming in and playing music and going “okay here you go, here’s some music that you’re going to like,” and then leaving, we’re are informed by the people, pretty much. This show is made for, by and with the people of the Isaac Region,’ she said.

By taking the time to truly engage with a region and its inhabitants, you can avoid the ‘fly-in, fly-out’ model of arts engagement, which Burton describes as a kind of cultural colonialism.

‘Plenty of people have plenty of opinions about the fly-in, fly-out model when it comes to the resources sector and when it comes to the cultural sector we can actually make the same mistake by flying in, committing, really, an act of arts colonisation. “This is excellent art and this is how we do it; this is the standard and this is the story you should tell” – and then buggering off again. And that has limited capacity for change, limited links to civic health and well-being, which are really demonstrated by long-term arts projects,’ he said.

Making time to make change

Incite Arts is a community-led organisation based in Alice Springs, where the company has worked with young people, people with disability, Aboriginal communities and other communities since 1998. One of the company’s signature events is the multi art-form, site-specific community collaboration Unbroken Land, a night time, promenade performance featuring performances by local choreographers, composers, filmmakers, designers, dancers, singers and storytellers.

Presented in both 2015 and 2016, the next Unbroken Land sees the project’s creative development timeline extended from one year to two.

Virginia Heydon, co-Artistic Director of Incite Arts, uses a cooking analogy when discussing the creation of the next Unbroken Land.

‘There have been two Unbroken Land events so far, and based very much on our experience of last year, we are now taking an even slower path. We recognise that not everyone works at the same pace, culturally or individually, and in recognition of the significance of some of the partners that we made connections with and are looking to make deeper connections with, we have decided to take an even slower path,’ she told ArtsHub.

‘I suppose we could say it’s like the slow food movement; it takes time to create to create a quality dish and similarly that’s the way we’re approaching this event.

‘There are such significant time demands placed on all of us and it’s only going to get harder and harder, rather than easier. So rather than try and compete on that level, it is a strategic decision to teach a completely different choice – and that can apply to the arts or any other aspect of our professional or personal life. It needn’t just be the arts,’ Heydon continued.

‘So you don’t always have to have your mobile phone on, for example. Good heavens, someone might have to leave a message and get you later. So that’s generally the way we’re going, and it is in response to both the economic and the human resource environment but I think the proactive way is to look at how we can solve things creatively rather than trying to fit a mould that is imposed on us. Good heavens, we’re all in the arts, you know? This is where we have our liberty, this is our job, so let us be innovative and responsible with our community development!’

Philosophy and social change

Scott Rankin, the co-founder, Creative Director and CEO of Big hART, has a similarly philosophical approach to art-making and the time required to generate lasting social change.

‘Say you’ve got a ticket for The Book of Mormon or the latest wild slaying of beasts at MONA or whatever it might be. That’s the longevity of it – just looking forward to exchanging your money for an experience. Or you can go, “I’m going to enter into the process of shifting the culture in which I live, via the ways in which narrative – in the broadest sense of using that word – narrates the future of the nation.” … And we’re all involved in what, whether we choose to help out or not; we’re all involved in that narration in some form,’ he said.

For Rankin, the process of making works such as Drive, The Namatjira Project and Acoustic Life of Sheds is just as important as the outcome.

‘Some people want to apply a virtuosic life commitment to the content [of a work] and we all recognise them in the Australian Art Orchestra or whoever it might be, and we go “Isn’t that marvellous, that’s what art is”. But there are other people who want to apply virtuosity to the process, and it may not have a recognisable, highly polished content outcome, and so people don’t notice the vast swathes of caregivers, of community builders, of volunteers … that are all part of this cultural narration that we are all potentially involved in,’ he said.

Projects like those run by Big hART, which to date has worked with 50 communities and 300 artists over its 25 years of operation to date, are developed over many years.

‘If you’re working for people who are outside the community or on issues that are invisible to the community; and you’re interested in bringing invisible narratives into the public domain, bringing things in front of the legislature or the political class so that there can be a shift in attitude, then you must walk very carefully,’ he explained.

‘You’ve got to begin these projects on these sensitive issues by going “let’s do no harm” at the very least. And then when you get beyond that, and begin to try and shift the reasons behind or the causes behind the issues that you’re trying to deal with, that also takes time. And then there’s the delivery of the art product itself, or the pieces that are going to be in a series so that you are giving people the cultural right of having their voice heard. And then there’s the beginning of the exit strategy, potentially, and then the legacy after you’ve gone. Now that’s, in very quick terms, that is a model that requires you to think in three to five year time frames,’ Rankin said.

The challenges of making slow art

Working on such long-term projects requires careful planning and implementation, said Heydon.

‘One significant challenge that we face in a small regional environment is when we’re dealing with agencies and institutions – schools and other partner groups – you have to have a key person that helps to drive the project … That person is critical to the success and the momentum of a project and a collaborative partnership,’ she explained.

‘Now, in this area we have a high turn-over of staff and personnel. So in a long term project like some of our arts and disability programs, we started working in 2005, so we’ve seen three school principals come and go in that time. In other agencies we’re faced with staff change-overs which can mean when I go to have a conversation with someone about their clients or a project that that organisation has been involved in, they don’t necessarily have the historical background; they don’t necessarily know what the blink I’m talking about. And so then they, understandably, aren’t as invested as their predecessor may have been.

‘So often we have to go back to grassroots. I will take a board member into a meeting with me, face to face; I will introduce us; I will try and give them the background and the relevance of the project or in the engagement with that organisation. And then I have to determine whether the partnership is going to fit into that person’s paradigm. Because if it’s not important to them, I can do all the communication in the world and I’m still going to hit a brick wall,’ she said.

QMF’s The Power Within faces an additional set of challenges that will be familiar to anyone from a city-based arts organisation who has worked regionally.

As Burton puts it: ‘Particularly when you’ve got metropolitan artists who are flying in and out, it is expensive. We’re a core team of about five or six flying out to central north Queensland once a month for the past six or seven months, and it’s expensive – so it takes a great deal of financial commitment from that point of view.

‘In addition it’s hard work because your artists are away from home and if you’re freelance artists that means it takes a great deal of scheduling and a great level of personal commitment from all of the artists involved.’

Additional challenges come with working on projects of scale across multiple locations, Burton continued.

‘We’re working in the Isaac Region at the moment and we’re effectively working in a council area that’s larger than Tasmania – and we’re working across six towns,’ he said.

‘I’ve written a show where we’re rehearsing a big dance number where one side of the stage will have people from Middlemount on it, and the other side of the stage will have people from Dysart on it – and they won’t meet each other until a week before the show is on! They’ve been rehearsing separately – and it’s similar with dramatic scenes, where we’ve got three or four characters who haven’t met each other yet. They’re rehearsing their scenes separately. That’s unique to this project.

‘Really, the challenges are unique to each region and each project … You’re always on your toes, so to speak, and adapting to each situation.’

An example: the Namatjira project

Big hART’s Namatjira Project – centred around an award-winning theatre performance telling the story of artist Albert Namatjira, and featuring members of his family on stage – is an illustration of how complex such long-term, community focused projects can be.

‘So, say the Namatjira family would like to work with Big hART because they are in this situation where they no longer own the copyright to their grandfather’s pictures and are in a pretty desperate situation in terms of poverty, explained Rankin.

‘They have limited opportunities for exploiting this cultural gift that they have amongst them across five generations, so is it possible to run an arts project that gets that story in front of the public, and does that through documentary and through an online platform, and does it through a touring show that’s highly successful in festivals etc?

‘Then behind that comes a strategy to build a legal entity which is a trust for the family, and to have the negotiations over many, many months – it’s now in its seventh year – to buy back the copyright; for the Australian public to be participating in buying back this iconic copyright for an iconic family, as part of a practical approach to remaking the relationships between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people,’ he said.

Not only does such a project have to work across election cycles; it has to be sustained whiles governments, ministers and staffers come and go. So why do it?

‘You’re going to have to continually maintain those relationships, you’re going to need $1.5 million a year approximately for a big strategy like that, and you’re going to have to be almost like a strategist or a general running a campaign – to use an unfortunate war image,’ Rankin said.

‘You’re going to need to be thinking in those ways about pre-empting the future as it’s coming at you. And that, to me, is the most exciting form of applied arts that’s really tapping into important issues, that’s making a choice to work on an issue like that. It’s exhilarating.’

Heydon is also effusive about working on such long-term, community focused projects. ‘I’ve got pictures on my wall of young adults who were in programs as a primary school student and are still involved in programs with us. It’s enormously rewarding,’ she said.

Getting started

Burton has two key pieces of advice for artists wishing to become involved in such long-term, community engaged projects.

‘I’ve been very lucky with QMF to have a fantastic, fantastic creative producer by the name of Marguerite Pepper, who’s done so many things across the country and across the world in terms of large scale events. And in terms of first steps it’s about having a great producer … And the other thing is time. So you really have to get on the phone and knock on doors and settle into a community and just talk – spend a lot of time talking and establishing trust, because that’s where everything comes from,’ he said.

Rankin’s advice is to make contact with the companies who are already engaged in such processes and try to find work with them – and but do your homework first.

‘There are very few companies – you can name them on one hand – who are creating works of great integrity over great lengths of time. If you look at Form in WA, or you look at Back to Back, or Big hART and the other companies that you’re citing, you’re starting to see very serious, very experimental, committed responses to narratives that are large and long term. And if I was a young artist now that’s where I could try and build my relationships, because they’re the people who know how to attract the funding to do that,’ he said.

‘So get to the companies who are doing great work … but you have to do a lot of research. You have to know, “oh that’s been happening for a long time, that’s where the thinking is up to.” And get into some comparative international work, because the best work is happening in WA at the same time as it’s happening in Alaska. You need to be across those kinds of practices that are coming from people who are working in very difficult domains with very difficult but fascinating issues.’