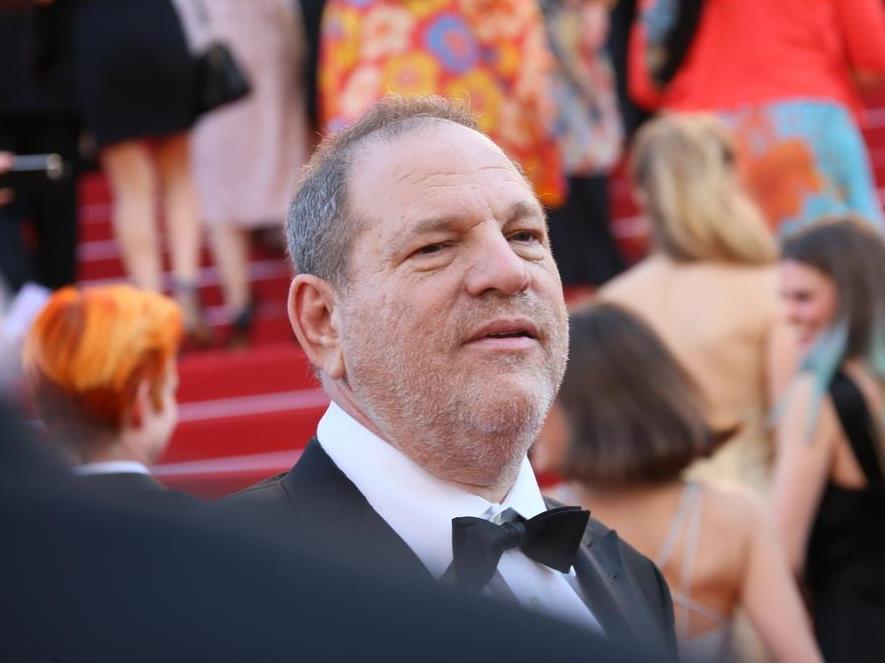

Harvey Weinstein at the Cannes Film Festival, May 2015. Photo by Denis Makarenko via Shutterstock.

Since the Weinstein scandal broke, our social media feeds have been flooded with #MeToo stories. Men are confronted by the magnitude of the problem, and women are confronted by how unsurprising the numbers are. And so, for the umpteenth time, we are looking at our industry and asking, “Why is it still happening?”

Theories abound, excuses poorly disguised as explanations: “Our work makes it confusing. What’s real? What’s acting?”; “We have such socially intimate work places,”; “We need freedom to play in order to be truly creative.” All rubbish. The truth is much simpler and far less forgiving: we have a problem with sexual harassment in our industry and beyond because men still believe in their own superior genius and the sanctity of their power, and cannot accept the equal value of women and the sanctity of our bodies. Because despite considerable efforts to reform the stories we tell about women, the stories we tell about and to men still reinforce these erroneous and dangerous delusions.

The Geena Davis Institute’s research applies gender performance theory (i.e. gender is a social construct which we make real through repetition) in the real world, liberating it from the constraints of academia and lofty leftist discourse. For example, the Institute’s research revealed a significant increase in girls’ enrolments in archery following the release of Pixar’s Brave, giving credence to the Institute’s slogan, “If she can see it, she can be it.” It’s an empowering message: we as story-tellers can change women’s lives by changing our stories.

When applied to our industry, gender theory’s primary site of criticism has been the lack of representation of working women, i.e. women with identities not inherently linked to their relationships with men, or the gendered imbalance of face time and talking time. Empowering women through representation is great, but it does implicitly reinforce the message that it is women who must change. While it would be disingenuous to call this victim blaming, per se, it is certainly burdening the oppressed with the responsibility of changing the world. It should not be incumbent upon women, fictional or otherwise, to be stronger, and prove they deserve respect, as if strength, conceived of (rightly or wrongly) as inherently masculine, is the only quality deserving respect. It should not be incumbent upon women to be less vulnerable in order to avoid or discourage assault, whether that means policing our dress or by battling our way through a systemically sexist industry to tell “our stories”, in order to teach girls they can be whatever they want to be, when we already know, from living “our stories” that we can’t. Because the Harvey Weinsteins of the world do not allow it to be so.

And why would they? Why would power brokers and star-makers like Weinstein want to produce status-quo busting women’s stories? It doesn’t serve them to empower women. How can you intimidate and harass a woman if she has a sense of her own agency, learned from the stories you funded?

That might sound sinister and conspiratorial, and it is tempting to argue that men like Weinstein aren’t really to blame because they don’t know what they’re doing, because they’re socialised just like women. But these days this conversation is so alive that such an argument is inherently dishonest. Men know there is a problem, and deep down they know the problem isn’t women.

We can have all the Meridas with their bows and arrows, Moanas with their boats and wit, Jessica Jones’ with their strength and resilience, but it doesn’t mean a thing if creeps like Weinstein and Number 45 still think the perfect woman looks like a Bond Girl and behaves like Betty Draper a la Mad Men season one, and the perfect man is any man who can exploit her sexually and domestically. If #MeToo has taught us anything, it’s that telling better women’s stories hasn’t really changed the lived experience of women, because it hasn’t really changed men. While criticising restrictive conceptions of femaleness is valid, it is only one of many strategies we need to co-ordinate in order to change the way women are treated. In real life.

That’s the big picture. More work for women actors where we don’t have to take off our clothes or be a warm prop in a man’s storyline would be amazing, but you know what would be more amazing? A life for women where we aren’t just an object for sexual conquest, a clothes rack (dressed or otherwise), and a footnote in our men-folks’ memoirs. It is time we started using our reach as storytellers to question the toxic construction of masculinity we have allowed to stand unchallenged, even as we’ve fought for our own liberation from similarly toxic, reductive, and destructive femininities.

On the one hand, the re-imagining of women and our awesome and infinite capacity and diversity needs to be continued and to conquer our representation in ‘men’s stories’. On the other hand, we must teach boys that they too can be anything they want to be, including kind, gentle, and respectful of women, and that such qualities do not threaten or diminish their manhood. Let’s teach men that sexual conquest is not their whole purpose any more than sexual servitude is a woman’s destiny. Lets teach men that it isn’t too late for them; that they are not powerless to resist their conditioning, and they are definitely not going to be excused if they don’t start doing better. That means, at a most basic level (and I can’t believe we still have to say this) not assaulting, stalking, harassing, or cat-calling women. It means men not accepting any of these behaviours in their mates. For our comrades in the creative industries, it means using their still larger platform to shake up the status quo and craft a new message.