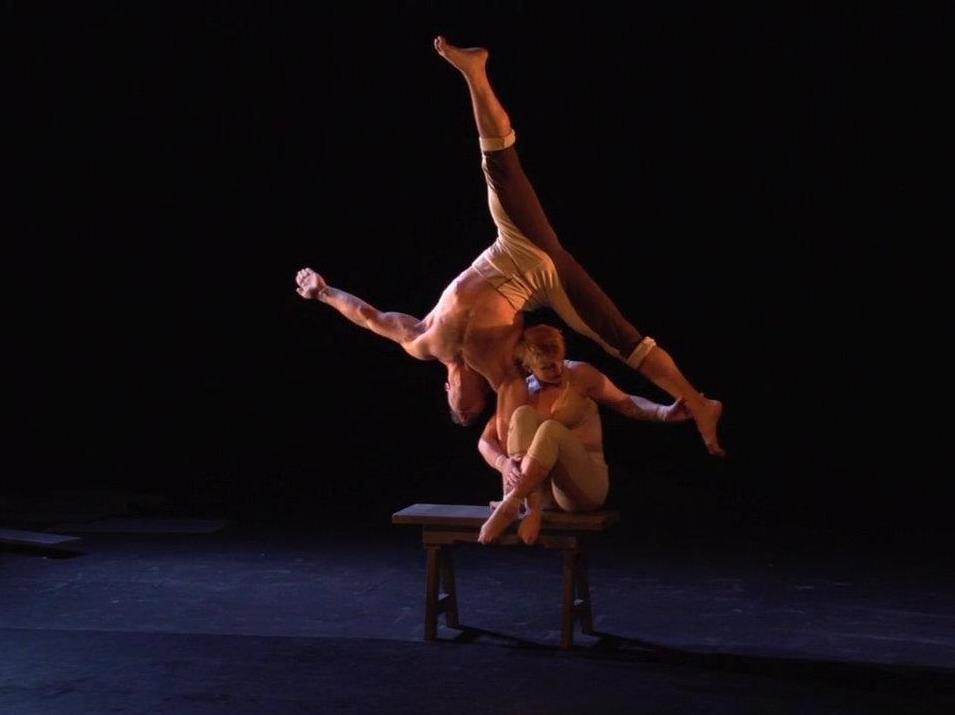

Casus Circus’ Finding the Silence. Image via Vimeo.

Born in the 1970s, and spearheaded by the likes of Welfare State International and clown Reg Bolton (UK), the Pickle Family Circus (USA), Christian Taguet’s Le Puits aux Images (France) and Australia’s own Circus Oz, nouveau cirque is a young art form, but one which has grown rapidly over just a few decades.

Today, companies such as the French-Canadian juggernaut Cirque du Soleil are virtually household names, thanks to a focus on spectacle and slickly produced entertainment that has wide and popular public appeal. But even as Cirque du Soleil tours more and more shows – the company’s website currently lists 20 different shows in production – other circus practitioners are taking their work in a very different direction, with impressive results.

By stripping away the glitz and glamour and focusing instead on the skilled physicality of finely-tuned bodies, companies such as acrobat (NSW), Gravity and Other Myths (SA) and Casus (QLD) are finding new ways to explore and advance circus as an art form.

As Casus Circus co-founder Emma Serjeant told ArtsHub earlier this year, ‘sometimes you just have to step back and look at the architecture of the body.’

‘Something that I kind of noticed especially in the last year, is that new circus is more and more taking on this role where it’s acceptable just to let the physical language of a circus show drive you through the show. Say, two years ago it was very hard to walk into a show and just have a guy juggling without justification … I think for me circus has been smothered in a narrative and people have been scared of just letting the circus do the talking,’ Serjeant said.

This focus on pure physicality is often accompanied by performances in more intimate settings, typified by Gravity and Other Myths’ A Simple Space, in which audiences are not only close to the action – they become part of it. This lack of window-dressing ensures more attention is paid to the physical craftsmanship on show; it also stimulates artists to evolve the art form as a consequence, as demonstrated by the latest Circus Oz production, Close to the Bone, now showing at the Melba Spiegeltent in Collingwood.

Here, the challenges of performing in a venue where the audience could literally reach out and touch the performers should they wish too, has resulted in the dramatic reinvention of that circus staple, the table-sliding routine.

Co-director of Close to the Bone, Debra Batton, described the value of constraint in an interview with ArtsHub last month, noting that ‘usually a table routine requires an enormous amount of space, because you run on it and off it from every direction. And we’ve discovered that by not having that possibility, we’ve created new language, new physical language, that we’ve never ever seen before in a table-sliding routine; and that’s purely because the space has determined that we find something else.’

This inventive approach to the circus arts is at odds with the house style of larger companies such as Canada’s Cirque Éloize and Brisbane’s Circa, both of which performed at this year’s Melbourne Festival in the decidedly impersonal space of Arts Centre Melbourne’s State Theatre. The performers in both companies display remarkable craft, but the impact and effect of such performances is significantly lessened when performed at a distance, resulting in an oddly passionless experience. Too, the choreography of Circa’s Yaron Lifschitz is aesthetically pleasing but increasingly closer to dance rather than true circus, while in the case of Cirque Éloize, projections further distract from the artistry.

This is even more pronounced in the performances of Cirque du Soleil, where props and set design work to enhance the spectacle at the expense of the actual performances, which again are at a considerable remove, save for those audiences who can afford the expensive VIP Rouge tickets. The company’s decision to render its performers anonymous via strictly enforced make-up designs and costumes (designed to ensure ubiquity across all touring versions of a given production) further emphasise the spectacle while reducing the focus on artistry.

Sequins and spectacle certainly have their place in circus arts – but if the focus is truly to be on the artistic side of the equation, then spectacle should not be allowed to dominate.

Five decades after contemporary circus burst onto our stages, the art form is at a crossroads. Either it focuses on growing its audiences via ever-larger and more extravagant shows; or it focuses on evolving the art, pushing the existing suite of circus skills into new directions by attending to craft instead of spectacle. Just possibly, it may do both, though at present that seems unlikely. It will be fascinating to see which of these conflicting drives wins out.