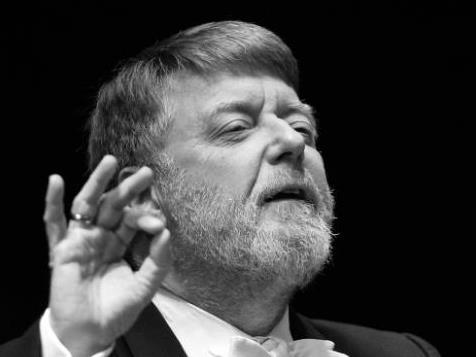

Image: Sir Andrew Davis via Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

The good fortune we enjoy of Sir Andrew Davis as the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra’s Chief Conductor brings the thought that these are very significant years in the history of the MSO. He provides every performance with a raft of experience, innate musicianship, a fine technique and an enthusiasm that summons unwavering commitment from the orchestra to give far more than expected. It is noteworthy that there is a distinct ‘sound’ the orchestra has developed under his clear direction without use of baton, characterised by careful voicing of chords, blend, spot-on tuning and powerful emotional depth.

This performance of all-20th-century music presented Ravel’s Piano Concerto for the Left Hand with distinguished French pianist Pierre-Laurent Aimard as soloist, and Mahler’s fifth Symphony. Both works present us with a similar issue: none of us are immune from suffering, loss and sadness, yet life depends upon each of us finding a way to manage.

The Concerto is a creation by a composer who never recovered from World War I (Ravel served as a stretcher-bearer and truck driver in the transport corps) who was commissioned to write a concerto for a concert pianist whose right arm had been amputated in the same conflict. In Mahler’s case it was more of a psychological trauma from chronic anxiety and hypersensitivity. Both works use the brutal and blunt instrument of the military ‘fanfare’ as a means of conveying this suffering.

The Ravel starts out of dark silence with deep-pitched, ruminating strings with the husky growl of contra-bassoon. We soon hear an ominous, descending scalic minor third; such a simple melodic gesture, but one which becomes key throughout this single-movement concerto. A tradition of French orchestration presents a firm penchant for bassoons, and the sonority of extreme bass keyboard, going back to Jean-Philippe Rameau; Ravel particularly savours the roar of the bottom octaves of a Steinway D. At all times fluid and subtle, with dazzling passages of brass and percussive elation, this work aches with sadness. An infamously difficult work to master, Aimard’s performance demonstrated a native Frenchman’s sympathy and understanding of sensibility throughout; his approach was always lyrical, effortlessly poised and delicate, though noticeably careful. A student of Messiaen’s wife, Yvonne Loriod, and the first pianist selected by Pierre Boulez as a member of the Ensemble Intercontemporain, Aimard gave a brilliant, bracing account of Boulez’s first two movements of Douze Notations as an encore with exquisite, acerbic bite.

At a time of turn-of-the-century optimism and exuberance, the first audiences of Mahler’s fifth Symphony were beguiled to discover that the work opens with an extended funeral march. Marked ‘with measured pace, stern, like a funeral procession’, it is tricky to get the tempo just right as it was on this occasion; one could almost hear soldiers’ boots scraping against gravel. What struck me hearing this well-known work again was its sheer scale. It was clear that Sir Andrew was a deft hand at pacing the performance so that passages of total mania and turmoil had ample punch and drive, such as the grinding, turbulent lower strings and violins gutturally playing out their theme on G string at the end of the second movement (Scherzo). There was also great subtlety of rhetoric throughout, such as the smooth-as-silk Adagietto, intended as a love letter but somehow infused with heart-wrenching, deeply tragic nostalgia. This movement, scored for strings alone and harp, was one of the most profound and affecting performances I have encountered. The Symphony ends with a giddy Rondo-Finale somewhat incongruously brimming with optimism, hope and high spirits. Drained after this emotional roller-coaster ride, I was left wondering what could possibly follow.

Tribute on this occasion should especially be paid to the magnificent brass section, particularly guest principal horn, Timothy Jones appearing courtesy of the London Symphony Orchestra.

Rating: Four stars out of five

Sir Andrew Davis conducts Mahler 5

Melbourne Symphony Orchestra

Sir Andrew Davis – conductor

Pierre-Laurent Aimard – piano

Ravel Piano Concerto for the Left Hand

Mahler Symphony No.5

Saturday 19 March 2016

www.mso.com.au