More than two centuries of colonisation leaves a lot of reparation behind it – generations of inequality and systemic prejudice.

In 2019, there are signs of hope. Culturally speaking, First Nations creators are being placed in the centre of arts policies across the nation and enabled in ways that didn’t exist a generation ago. But what would really create change?

According to Pam Bigelow, Manager, Indigenous Art Centre Alliance, what’s needed in 2020 is political will.

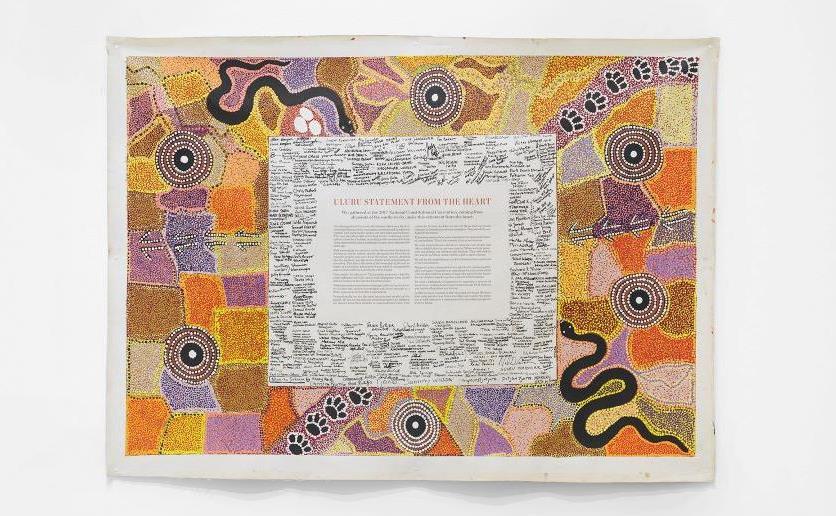

‘Government acceptance of the Uluru Statement from the Heart [Uluru-ku Tjukurpa] and a Treaty would be a massive move forward for modern Australia,’ she said. ‘And, of course, adequate funding and resources for remote Indigenous Community Art Centres nationwide, so that artists from the oldest culture on earth can reach their full potential.’

Bigelow knows what she’s talking about, as she’s been at the centre of bringing together artworks from Far North Queensland for a major exhibition, Belonging, that will open at the National Museum of Australia before touring nationally. Together, the Art Centres work with over 500 artists and come under the Indigenous Art Centre Alliance (IACA).

Read more: A new age of appreciation for First Nations visual arts

John Armstrong, Art Centre Manager at MIArt/Mirndiyan Gununa Aboriginal Corporation, is similarly pragmatic, beginning with the larger political structure.On his wishlist is ‘a co-ordinated policy between the Federal and State governments, recognition of Aboriginal arts centres as economic hubs, for more funding agencies to actually come to visit and see what’s happening on the ground, and a tripling of our grant funds’.

‘It would be fantastic,’ he said. ‘But it’s not going to happen.’ Travel costs are a major expense for MIArt – a trip to Darwin Art Fair cost them around $50,000 in airfares alone – so initiatives such as travel subsidies would be a big help in their work.

Read more: Behind MIArt’s incredible paintings is the work you don’t see

Erub artists at work. Courtesy Erub Arts, Image by Lynnette Griffiths, courtesy Erub Arts.

Erub artists at work. Courtesy Erub Arts, Image by Lynnette Griffiths, courtesy Erub Arts.

Distance is was also an issue for Lynnette Griffiths. She is Artistic Director of Erub Arts, an arts centre located on Erub (Darnley Island), the most north-eastern of the Torres Strait Islands that has had to forge global links for it work. She would love wider Australia to embrace the richness of First Nations arts.

Her wish is that firstly Australia would ‘recognise good art as valid with the correct acknowledgement of its creators, no matter where or how it develops’.

‘Then creating spaces for this art to be shown, so collectively we can celebrate and discuss the richness, diversity and unique insights that all art brings to peoples’ lives,’ she said.

Read more: Small island arts centre Erub Arts at heart of global Ghost Net movement

For Patricia Adjei, Arts Practice Director First Nations Arts and Culture at the Australia Council, the major change she’d like to see through 2020 is a greater focus on skills for First Nations artists.

‘It would be really great to see more recognition of First Nations artists – more awards, more fellowships and residency programs,’ she said. ‘Just more opportunities to develop their practice, the chance to collaborate nationally and internationally.

‘I’d love to see more skills development in different sectors.’

The Australia Council’s focus on First Nations artists includes some of the biggest national awards to recognise Indigenous creative achievement. They are now calling for nominations for the Red Ochre and Dreaming Awards.

Read more: Dreaming of transformation

Rachel Bin Salleh is the Publisher of Magabala Books. Located in Broome, it’s notable for being the most remote publisher in Australia, but more importantly Magabala solely publishes works by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander storytellers, poets, writers and illustrators.

For Bin Salleh, the first change she’d like to see is the increasing recognition of First Nations artists as leaders across all artforms. ‘[And] growing audiences and recurrent funding secured for First Nations controlled and led organisations,’ she said.

Read more: The tyranny of distance and an iconic Australian publisher

Jennifer Bott AO, CEO of NIDA, also wants a formal embrace of the Uluru Statement from the Heart. ‘[It] will mean a seismic shift in our nation’s recognition of our history,’ said Bott. In a year that marks 250 years since the The Endeavour came to Australia, acknowledging an Indigenous-created document that acknowledges the ongoing ownership and continuing culture would be significant.

Also on her wishlist: ‘For First Nations storytellers to own a greater share of the mainstream Australian narrative – for their stories to be told at primetime, and reach Australians from all walks of life. For our part, we hope that our newly founded Student Fund and Indigenous Strategy Group will support more First Nations artists to join us at NIDA,’ Bott added, looking at how her own organisation could contribute.

Read more: Career spotlight on Indigenous dancer and change-maker

As Festival Director of Word for Word, Rochelle Smith’s wish is that everyone would read a particular book – Bruce Pascoe’s award-winning Dark Emu.

‘Dark Emu is a re-writing of this country’s history. A truer history. One that white Australians – myself included – were never taught,’ she said. ‘It’s about how the First People of this land not only lived, but thrived, for millennia. It covers everything from art to agriculture and subverts the perception of Australia as a barren, desolate place where crops failed and Aboriginal people just subsisted. It opens our eyes and allows us to blink away the fog of misinformation perpetuated by our post-colonial society.’

She said it was her fervent hope that he will return to the festival in 2020 with his new children’s version, Young Dark Emu: A Truer History.

Read more: Traditional owners are the focus of Geelong writers festival

For Edwina Palmer, Judge and Director of Ravenswood Australian Women’s Art Prize, her wish is simple.

‘Our wishlist is that this prize offers a great new opportunity for emerging Indigenous artists,’ she told ArtsHub. And for artists every opportunity means the chance to build their career and continue their practice into 2020.

Read more: New prize for emerging Indigenous artists for 2020